|

City of Gold is a big adventure, a tale of two brothers and two mules, an odyssey in three weeks. Tell us how it began. A single image sparked it, in a book about my home mountains, the San Juans of southwest Colorado. Back in Telluride’s mining heyday, before the mule trail up to the Tomboy Mine was made into a wagon road, a mule carried the core piece of a new transformer six miles up to the mine. This was an astounding feat. The pack mules usually carried 300 pounds, and this load weighed 700. I thought that would be so great in a novel. So it all began with Hercules. Did his name come to you right away? My first thought was, it should be heroic. My second was, it had to be Hercules. That led to daydreaming his backstory. Was he one of a plow team? The other mule should be called … Peaches. The beginnings of a plot began to suggest itself. Hercules and Peaches belong to a farming family in Hermosa, on the Durango side of the mountains. They’re stolen by a rustler. Hercules gets sold to the Tomboy Mine. And what about Peaches? This makes 20 novels for you. You haven’t written one set in southwest Colorado since your second and fifth novels, Bearstone and its sequel, Beardance. They were contemporary and had to do with Colorado’s last grizzlies. I hadn’t written a historical novel since Jason’s Gold and Down the Yukon, dramatizing the Klondike gold rush and the rush to Nome. With this new project my goal was to bring to life the same gold-obsessed era in the San Juans of southwest Colorado. Jean and I had been visiting the mountain towns of Silverton, Ouray, and Telluride for decades. Researching their mining history would turn up no end of grist for a novel blending fictional characters and events with real-life people and events. Why did you choose Telluride, not Silverton or Ouray? All three had spectacular settings and amazing histories, but Telluride had Butch Cassidy and a notorious marshal, James Clark. Butch’s first-ever bank robbery was in Telluride (June, 1889) and many locals in Telluride suspected that Jim Clark, out of town that day, was in cahoots. After reading a biography of Butch Cassidy and researching the marshal, I was looking for a way to weave them into the plot. My historical novel would also be a Western. Tell us about this photo you took looking down on Telluride.

I took it in late September, the same week of the year when Owen first lays eyes on Telluride. He was standing atop Ingram Falls (out of the picture to the right but not by far) as the weather is breaking, having survived an early winter storm in the high passes. He stumbles onto the valley floor at the mills of Pandora, at the right-side edge of the photo. Note the mule trail leaving Telluride in left center, now a 4-wheel drive road. Follow its route as it angles up and through the red cliffs to the Smuggler-Union and the Tomboy, the mines I featured in the story. At the time, they were Telluride’s richest. They’re in the upper right quadrant of the photo, at timberline in the Marshall and Savage Basins. Was Telluride’s motto back then actually “City of Gold”? It was. I came across it in a 2016 publication of the Mining History Association, whose annual conference was held in Telluride that year: “By 1896, two-thirds of the district’s $3 million in ore production came from gold, and only a year later, this value jumped to an estimated $25 million. Gold production was so robust that the town adopted the motto “City of Gold.” For trivia buffs, this makes two titles that I took from the motto of a town. The other novel and town? Never Say Die and Aklavik, in Canada’s Northwest Territories. Tell us about your choice of 1900 as the year to set the story.

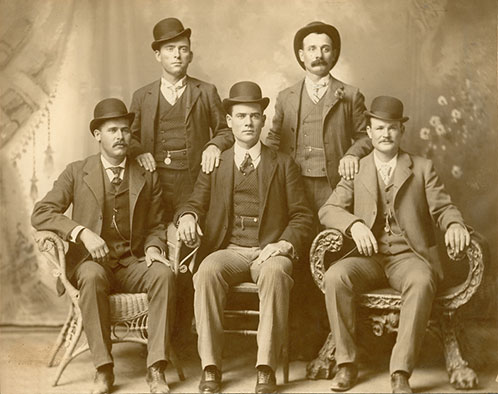

1900 was the year the famous photo of Butch and his “Wild Bunch” was taken in a photography studio in Fort Worth, Texas. Butch and his gang were on a lark, and apparently didn’t realize it could be duplicated. Before long, as the marshal informs Butch in my story, it was “in every post office in the country.” Historians believe that the photo had much to do with Butch and Sundance fleeing to South America early in 1901. I got to thinking that my novel could take place in the fall of 1900, when the photograph first shows up in Telluride. Butch is seated on the right. The Sundance Kid is seated on the left. How far back does your interest in Westerns go? I was born to it. The man I’m named after, my great-grandfather Will Rhodes, was the marshal of Dodge City, Kansas for 10 years, starting in 1892. For a photo of me and my two older brothers in our Hopalong Cassidy outfits, check out the “Just For Fun” section of my website. Let’s shift to the farming family whose mules are stolen in Chapter One. In your Author’s Note you mention that the Hollowells are fictional. Tell us about them, beginning with Owen. Whittled down, every story begins with a character who has a problem. Now that I had a novel-worthy problem--recovering those mules—I needed a protagonist to go after them. “Owen” sounded like a good fit with the time period. Owen has recently lost his father to tuberculosis, the “family curse” as his mother calls it. He only has his mother and little brother, and the heavy lifting is going to be up to him. How did you land on tuberculosis? Back then, TB was a dread disease, commonly called “consumption.” In the 1890s, people were coming from hither and yon to Colorado in hopes of escaping it. Colorado’s climate, especially its dry air, promised a safer place to live, and there was something to that. Till is a character in more ways than one. He’s nine years old and something of a loose cannon, quite the foil to Owen. At the outset, did you have an idea how vital to the story Till would become? Not at all. As Owen is leaving, on foot, and Till is insisting he’s going along, Ma says something like “Oh, no you’re not, you’re too young for the mountains.” Those were my sentiments, exactly. It was only after Owen had been in Telluride for a number of chapters that I heard Till calling, “Put me in, coach, I’m ready to play.” Soon as he showed up on the train, my fingers started to fly. You can’t leave a player with that much talent on the bench. You cast Mary Hollowell and her boys as having only recently arrived from eastern Kansas, outside of Lawrence. Do you have family history there? Edmund O. Rhodes, my grandfather—born and raised in Dodge City, in western Kansas—graduated from the University of Kansas in Lawrence. I have a connection with both towns myself, with fond memories from early in my travels as a writer. That was part of it, but mostly it had to do with Telluride’s marshal, James Clark, a difficult man with a violent past. It occurred to me that the marshal’s history could be intertwined with the history of the Hollowell family, going back to the burning of Lawrence during the Civil War. Clark rode with Quantrill’s Raiders, and the Hollowells were among the many Quakers who had settled there to help the cause of Kansas Territory becoming a free state, rather than a slave state, when the time came to enter the Union. Landscape is a key factor in City of Gold, from the mountains to the canyons.

All the way back to Bearstone, I’ve been taking my readers into the wild places that have been a big part of my life. City of Gold opens close to home in Hermosa, up the Animas Valley from Durango. Owen’s solo trek on foot into the high San Juan Mountains takes him up through the forests, onto the tundra, and over Black Bear Pass, at 12,840 feet. It felt good to be writing about our spectacular high country again. Just recently I got around to compiling the backpack trips I’ve taken with family and friends in the Weminuche Wilderness, a preserve of 760 square miles within the San Juans. Most of those trips were a week long; over the years, my time in the Weminuche added up to seven months. We usually visit a half-dozen or so of the high lakes. While Owen is in Telluride, Molly takes him up to Blue Lake, her favorite place. Here’s a photo I took of Ice Lake, about six miles from Blue Lake as the raven flies. Some of the novel’s locations in southeast Utah’s canyon country, including Natural Bridges, must be favorites of yours. To be sure. From Bears Ears Pass on the old wagon road from Blanding to Hite City, Owen was looking down on Cedar Mesa with its myriad canyons, including Grand Gulch. Over several decades, Jean and I went on numerous dayhikes and backpack trips in those dozen or so canyons, enraptured with their countless ruins and rock art dating back a thousand years and more. Bears Ears National Monument, as originally established by President Obama, provided protection for all of Cedar Mesa and much, much more. Considering all the research you did for City of Gold, what surprised you the most? Growing up, I had learned about the era of the Robber Barons in history books, but until I looked into the 1890s in Telluride, I had only a vague understanding of how bad those times were for the working poor. Learning the details of what it was like for the miners was a real eye-opener. What are your hopes for City of Gold? Mostly, that it’s a whopping good tale. I hope it fosters the pleasure and value of reading historical fiction. At the same time, I hope it encourages young people to stretch their legs in the wild places. Nearly all my books are set in our priceless public lands, which will always need protecting. Aldo Leopold put it best: “I’m glad I shall never be young without wild places to be young in. Of what avail are forty freedoms without a wild place on the map?” You’ll find much more about the writing of City of Gold in Will’s Author’s Note at the end of the novel. |

|